A tall order for PNG to become a rice exporter by 2030

News that matters in Papua New Guinea

|

| A farmer drying harvested paddy in Merauke (Indonesia). - Pic courtesy of The National. |

A tall order for PNG to become a rice exporter by 2030

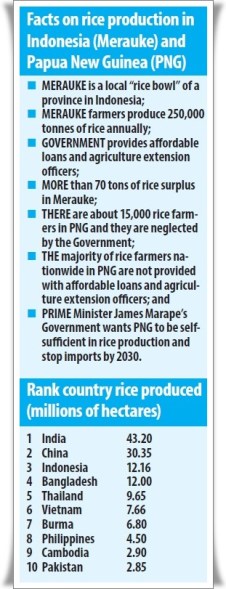

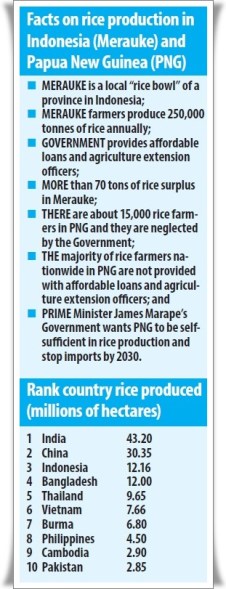

PORT MORESBY: Prime Minister James Marape had boldly announced that he wants Papua New Guinea to be self-sufficient in rice production by 2025 and to be rice exporter by 2030.

According to a news report in The National, the Government would need to support some 15,000 rice farmers nationwide in the bid to steer PNG towards self-sufficiency.

The Government also needs to support many others measures to ensure it achieves its targets.

This is the full report as published by The National:

Support 15,000 rice farmers in PNG towards self-sufficiency

The National’s senior reporter CLIFFORD FAIPARIK visited Merauke City on Oct 18 and 19 just across the PNG-Indonesia border and found that Papua New Guinea (PNG) has much to learn from the Indonesians on rice production and reducing imports.

RICE is the unofficial staple food for PNG. Although Papua New Guineans consider rice their staple, it is not produced or cultivated commercially on a large scale nationwide.

Instead, PNG imports up to K700 million annually from Thailand, Vietnam and Australia.

And Prime Minister James Marape has set the Government’s plan and target to stop rice imports by 2030.

He said a business incubation park, costing about K2 million, would be built next year for Papuan New Guineans engaged in Micro Business Small to Medium Enterprise (MBSME’s) to venture agriculture activities, like rice farming, to grow local PNG’s businesses.

After all, PNG has large swampy and flood plain areas to grow rice on large commercial scales.

“PNG can be a supplier of rice to countries like the Philippines where rice is a staple food eaten three times a day. Currently, PNG is importing rice from Australia.

“PNG can reverse the trend and supply rice to Australia. PNG has the potential in rice cultivation. But we have to be committed and work hard,” he added.

A visit to the Merauke Regency (District), just across the PNG-Indonesia border, would be convincing enough for one to truly believe PNG can realise the aim of becoming self-sufficient in rice production.

However, Papua New Guinean rice farmers must learn how to cut costs in rice production or cultivation.

One way to reduce production cost is to focus rice cultivation in swampy and wet terrrains like in the PNG border provinces of Western and Sepik.

Such production is also possible by engaging and encouraging small rice farmers with the Government acquiring land, providing small affordable loans and technical advice.

Such initiatives by the Merauke Local Government some 20 years ago have resulted in a surplus production of cheap organic rice today.

Merauke has more than 200,000 tonnes of rice stored in mills and there is no market.

About 250,000 tonnes of rice is produced annually in Merauke but local consumption is only 25,000 tonnes.

The rice in Merauke is organic because cultivation is by traditional rice farming methods that do not use chemicals or pesticides.

Instead, PNG imports up to K700 million annually from Thailand, Vietnam and Australia.

And Prime Minister James Marape has set the Government’s plan and target to stop rice imports by 2030.

He said a business incubation park, costing about K2 million, would be built next year for Papuan New Guineans engaged in Micro Business Small to Medium Enterprise (MBSME’s) to venture agriculture activities, like rice farming, to grow local PNG’s businesses.

After all, PNG has large swampy and flood plain areas to grow rice on large commercial scales.

“PNG can be a supplier of rice to countries like the Philippines where rice is a staple food eaten three times a day. Currently, PNG is importing rice from Australia.

“PNG can reverse the trend and supply rice to Australia. PNG has the potential in rice cultivation. But we have to be committed and work hard,” he added.

A visit to the Merauke Regency (District), just across the PNG-Indonesia border, would be convincing enough for one to truly believe PNG can realise the aim of becoming self-sufficient in rice production.

However, Papua New Guinean rice farmers must learn how to cut costs in rice production or cultivation.

One way to reduce production cost is to focus rice cultivation in swampy and wet terrrains like in the PNG border provinces of Western and Sepik.

Such production is also possible by engaging and encouraging small rice farmers with the Government acquiring land, providing small affordable loans and technical advice.

Such initiatives by the Merauke Local Government some 20 years ago have resulted in a surplus production of cheap organic rice today.

Merauke has more than 200,000 tonnes of rice stored in mills and there is no market.

About 250,000 tonnes of rice is produced annually in Merauke but local consumption is only 25,000 tonnes.

The rice in Merauke is organic because cultivation is by traditional rice farming methods that do not use chemicals or pesticides.

Surtano … has 200 tonnes of rice to sell

Rice farmer Surtano says he has 200 tonnes of rice stored in a rice mill and “we are looking for buyers”.

“Merauke supplies rice to Papua and West Papua provinces in Indonesia. With the surplus, we are looking at supplying to PNG,” he added.

Surtano said: “I was able to secure this 10ha to cultivate rice with the Government’s assistance. They provided funds to me through a loan scheme and I built my first rice mill for 170 million Rupiahs (about K20,000) 10 years ago.

“I use manual labour to work on my rice fields and also mill it. I have now paid off my first loan and got another loan to buy machinery, like four cars, a truck and a tractor and also paid off that loan within six years.

“I have 13 employees, including a tractor operator. My rice farming is more high technology now. I also buy rice from other farmers and mill them,” he added.

Surtano said each family usually had about five hectares to plant rice paddy, with a hectare producing about three tonnes of rice.

“Famers harvest their rice, sell to the mill at about 500 rupiah (about K1) per kilo. We have two options after milling the rice.

“We sell it to the Government warehouse for 8,000 rupiah (K2) per kilogramme to private warehouses for 10,000 Rupiah (K2.50) per kilogramme.

“The Government buys the rice from the mills and store in warehouses. And the Government also gives rice to public servants,” he added.

Surtano said Government agriculture extension officers conducted regular inspections for quantity and quality.

He added that in one village in Merauke, it had 500 rice farmers because the terrains were ideal for rice cultivation.

“Merauke supplies rice to Papua and West Papua provinces in Indonesia. With the surplus, we are looking at supplying to PNG,” he added.

Surtano said: “I was able to secure this 10ha to cultivate rice with the Government’s assistance. They provided funds to me through a loan scheme and I built my first rice mill for 170 million Rupiahs (about K20,000) 10 years ago.

“I use manual labour to work on my rice fields and also mill it. I have now paid off my first loan and got another loan to buy machinery, like four cars, a truck and a tractor and also paid off that loan within six years.

“I have 13 employees, including a tractor operator. My rice farming is more high technology now. I also buy rice from other farmers and mill them,” he added.

Surtano said each family usually had about five hectares to plant rice paddy, with a hectare producing about three tonnes of rice.

“Famers harvest their rice, sell to the mill at about 500 rupiah (about K1) per kilo. We have two options after milling the rice.

“We sell it to the Government warehouse for 8,000 rupiah (K2) per kilogramme to private warehouses for 10,000 Rupiah (K2.50) per kilogramme.

“The Government buys the rice from the mills and store in warehouses. And the Government also gives rice to public servants,” he added.

Surtano said Government agriculture extension officers conducted regular inspections for quantity and quality.

He added that in one village in Merauke, it had 500 rice farmers because the terrains were ideal for rice cultivation.

Hoko … rice farming in PNG started in the 90s

PNG’s Agriculture and Livestock (DAL) irrigation agronomist Heai Steven Hoko said: “We have been working and cultivating rice similarly to Merauke.

“But the Government is not supporting us. Currently, the big players in the rice industry are importing rice from Thailand, Vietnam and Australia.

“The rice are repacked into local brand names and reselling to us. But we can be self-sufficient and grow our own rice like what is happening in Merauke.

“We can break the monopoly by encouraging small rice farmers to produce rice. The current major rice importers are very adamant about remaining dominant in the local rice market.

“They don’t allow new investors to come in and develop large-scale commercial rice production in the country.”

Hoko said that small rice farmers started in the 1990s under the Food Agriculture Organisation (FAO) programme.

“At that time, we were known as special project on security and that DAL was switching its focus according to what is happening in the world.

“Food security is ever changing and evolving globally, changing views regularly. We then changed from a food management branch to food security branch.

“We had technical cooperation assistance and one was rice covering food security in a broader scope. And one of the assistance we got was from the so Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA),” he added.

Hoko said: “We kicked off the project in 2003 on food security by empowering farmers in rice cultivation. The project ended in 2015. Our aim was to increase rice production in the country and to do away with the concept of large commercial rice.

“So we empowered farmers to grow and eat themselves. This, we learnt from the Vietnamese and Japanese who are today leading rice producers.”

Although rice was introduced by early missionaries, it was already cultivated during the colonial days when the Australian colonial government was planting paddy in Bereina, Central Province and Bainik in East Sepik.

“We also started planting paddy in Madang, Morobe, Central, Manus, Milne Bay and East Sepik as encouraged by DAL. Our module is small rice farming systems because we don’t have large mechanised rice farming.

“But we want to focus on subsistence rice farmers. If our people want to grow rice, we use the system that our Government is working on. So our investment is training our agriculture extension officers, giving small tools to the rice farmers rather than pushing for large scale farming. So that’s how we went out to help in provinces that had started rice cultivation,” he added.

Hoko said Maprik in Sepik was one place where farmers were found enthusiastically planting rice.

“They planted paddy in their gardens just like ordinary yams and bananas. So DAL started assisting them. And from working with the farmers, we realised that rice farming was viable although rice is not a traditional food. But then the farmers needed skills and we realised that the district officers also lacked rice farming techniques.

“They needed skills like harvesting, drying, milling and storing unlike our traditional food like growing kaukau, taro, banana that had to be consumed fast before they go bad.

“For rice, we can harvest and store it and you need machines to process rice. So, technical training is required for our enthusiastic rice farmers. This is why we are organising trainings for farmers at the Japanese-funded Organisation for Industrial, Spiritual and Cultural Advancement (OISCA) centre in Warango, East New Britain where farmers are trained to develop their skills and rice farming culture of sending their harvest to millers,” he added. When the project ended in 2015, we found that the number of paddy farmers had ballooned and production had increased.

“For rice, we can harvest and store it and you need machines to process rice. So, technical training is required for our enthusiastic rice farmers. This is why we are organising trainings for farmers at the Japanese-funded Organisation for Industrial, Spiritual and Cultural Advancement (OISCA) centre in Warango, East New Britain where farmers are trained to develop their skills and rice farming culture of sending their harvest to millers,” he added. When the project ended in 2015, we found that the number of paddy farmers had ballooned and production had increased.

“And in Maprik alone, farmers planted rice in normal gardens of about 2,000 sq m. If they go higher, they will need labour to weed the land.

“Such farmers can harvest about 400kg of rice. And a family of six children can produce about 40 bags of 10kg rice from a garden in a year,” he said.

Hoko said the famers don’t eat all the rice at once, so they dry and store it because they also eat other produce like bananas.

“Only when they want to eat rice, they take the grain to the Government mills and pay 50 toea per kg to mill their grain. The rice can last them four months,” he added.

Hoko said the project started with 2,000 famers in East Sepik (Maprik and Angoram) and ended with 8,000 farmers in 2015.

“At one stage, there were 20,000 famers in East Sepik alone. But, overall, we had 15,000 farmers on record in the provinces that we started cultivating paddy (Madang, Morobe, Central, Manus, Milne Bay and East Sepik).

“But rice farming was very successful in East Sepik, especially in Maprik. Unfortunately, after the project ended, we left and did not follow up due to absence of funds.

“The then Government committed to financing the 2017 General Election and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (Apec) leaders’ summit in 2018.

“Today, we still don’t have the money to go out to check on the farmers,” he added.

Hoko said the only way for PNG to go into mass rice production was to empower rice growing in villages.

“Training and funding are needed because we have to cultivate rice farming culture into us. After that we can go into large-scale commercial fully-mechanised irrigated hi-tech rice farming.

“Form the project, we found that it is possible for us to grow rice and be self-sufficient. But the strategy, some senior government officers are thinking, is bringing someone from outside. Bringing in an investor to start producing rice and we meet our goal in rice production domestically. The disadvantage is the investor comes to make big money, reap profits. So, what is there left for our people?

“Our Prime Minister James Marape said that by 2025 we must eat our own rice. So, the Government needs to give us seed money and we invest in Sepik and other plains like Central, Western, Gulf Madang, Oro and Milne Bay.

“We can do it if we have money, knowledge, technical skills at our fingertips. All we need is to work with our people. I have made a submission for the Government to support small rice farmers.

“We also have to empower our agriculture extension district officers through the District Development Authority (DDA).

“The Government put provides the capital, we empower famers by securing rice and water. We cut down on rice imports,” Hoko said.

He estimated an annual rice production of 20,000 tonnes under the project that “we already have a developed mechanism”.

Hoko said: “We have 15,000 paddy farmers nationwide. If each farmer can produce and mill 185kg of rice, it means a saving of about K740 annually on spending K36 on a 10kg rice bag.

“Altogether these famers can save about K11 million annually from cutting down rice imports how massive production will be with full Government support and funding.”

“But the Government is not supporting us. Currently, the big players in the rice industry are importing rice from Thailand, Vietnam and Australia.

“The rice are repacked into local brand names and reselling to us. But we can be self-sufficient and grow our own rice like what is happening in Merauke.

“We can break the monopoly by encouraging small rice farmers to produce rice. The current major rice importers are very adamant about remaining dominant in the local rice market.

“They don’t allow new investors to come in and develop large-scale commercial rice production in the country.”

Hoko said that small rice farmers started in the 1990s under the Food Agriculture Organisation (FAO) programme.

“At that time, we were known as special project on security and that DAL was switching its focus according to what is happening in the world.

“Food security is ever changing and evolving globally, changing views regularly. We then changed from a food management branch to food security branch.

“We had technical cooperation assistance and one was rice covering food security in a broader scope. And one of the assistance we got was from the so Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA),” he added.

Hoko said: “We kicked off the project in 2003 on food security by empowering farmers in rice cultivation. The project ended in 2015. Our aim was to increase rice production in the country and to do away with the concept of large commercial rice.

“So we empowered farmers to grow and eat themselves. This, we learnt from the Vietnamese and Japanese who are today leading rice producers.”

Although rice was introduced by early missionaries, it was already cultivated during the colonial days when the Australian colonial government was planting paddy in Bereina, Central Province and Bainik in East Sepik.

“We also started planting paddy in Madang, Morobe, Central, Manus, Milne Bay and East Sepik as encouraged by DAL. Our module is small rice farming systems because we don’t have large mechanised rice farming.

“But we want to focus on subsistence rice farmers. If our people want to grow rice, we use the system that our Government is working on. So our investment is training our agriculture extension officers, giving small tools to the rice farmers rather than pushing for large scale farming. So that’s how we went out to help in provinces that had started rice cultivation,” he added.

Hoko said Maprik in Sepik was one place where farmers were found enthusiastically planting rice.

“They planted paddy in their gardens just like ordinary yams and bananas. So DAL started assisting them. And from working with the farmers, we realised that rice farming was viable although rice is not a traditional food. But then the farmers needed skills and we realised that the district officers also lacked rice farming techniques.

“They needed skills like harvesting, drying, milling and storing unlike our traditional food like growing kaukau, taro, banana that had to be consumed fast before they go bad.

“For rice, we can harvest and store it and you need machines to process rice. So, technical training is required for our enthusiastic rice farmers. This is why we are organising trainings for farmers at the Japanese-funded Organisation for Industrial, Spiritual and Cultural Advancement (OISCA) centre in Warango, East New Britain where farmers are trained to develop their skills and rice farming culture of sending their harvest to millers,” he added. When the project ended in 2015, we found that the number of paddy farmers had ballooned and production had increased.

“For rice, we can harvest and store it and you need machines to process rice. So, technical training is required for our enthusiastic rice farmers. This is why we are organising trainings for farmers at the Japanese-funded Organisation for Industrial, Spiritual and Cultural Advancement (OISCA) centre in Warango, East New Britain where farmers are trained to develop their skills and rice farming culture of sending their harvest to millers,” he added. When the project ended in 2015, we found that the number of paddy farmers had ballooned and production had increased.“And in Maprik alone, farmers planted rice in normal gardens of about 2,000 sq m. If they go higher, they will need labour to weed the land.

“Such farmers can harvest about 400kg of rice. And a family of six children can produce about 40 bags of 10kg rice from a garden in a year,” he said.

Hoko said the famers don’t eat all the rice at once, so they dry and store it because they also eat other produce like bananas.

“Only when they want to eat rice, they take the grain to the Government mills and pay 50 toea per kg to mill their grain. The rice can last them four months,” he added.

Hoko said the project started with 2,000 famers in East Sepik (Maprik and Angoram) and ended with 8,000 farmers in 2015.

“At one stage, there were 20,000 famers in East Sepik alone. But, overall, we had 15,000 farmers on record in the provinces that we started cultivating paddy (Madang, Morobe, Central, Manus, Milne Bay and East Sepik).

“But rice farming was very successful in East Sepik, especially in Maprik. Unfortunately, after the project ended, we left and did not follow up due to absence of funds.

“The then Government committed to financing the 2017 General Election and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (Apec) leaders’ summit in 2018.

“Today, we still don’t have the money to go out to check on the farmers,” he added.

Hoko said the only way for PNG to go into mass rice production was to empower rice growing in villages.

“Training and funding are needed because we have to cultivate rice farming culture into us. After that we can go into large-scale commercial fully-mechanised irrigated hi-tech rice farming.

“Form the project, we found that it is possible for us to grow rice and be self-sufficient. But the strategy, some senior government officers are thinking, is bringing someone from outside. Bringing in an investor to start producing rice and we meet our goal in rice production domestically. The disadvantage is the investor comes to make big money, reap profits. So, what is there left for our people?

“Our Prime Minister James Marape said that by 2025 we must eat our own rice. So, the Government needs to give us seed money and we invest in Sepik and other plains like Central, Western, Gulf Madang, Oro and Milne Bay.

“We can do it if we have money, knowledge, technical skills at our fingertips. All we need is to work with our people. I have made a submission for the Government to support small rice farmers.

“We also have to empower our agriculture extension district officers through the District Development Authority (DDA).

“The Government put provides the capital, we empower famers by securing rice and water. We cut down on rice imports,” Hoko said.

He estimated an annual rice production of 20,000 tonnes under the project that “we already have a developed mechanism”.

Hoko said: “We have 15,000 paddy farmers nationwide. If each farmer can produce and mill 185kg of rice, it means a saving of about K740 annually on spending K36 on a 10kg rice bag.

“Altogether these famers can save about K11 million annually from cutting down rice imports how massive production will be with full Government support and funding.”

Comments

Post a Comment